Because I’m apparently incapable of staying out of trouble lately, I got into a discussion on Mike Shatzkin’s blog the other day about advances and earn-out. In discussing Hugh Howey’s comparison of earnings for authors in traditional publishing versus self-publishing, Mike (who’s an industry consultant) pointed out that it’s hard to pinpoint a traditionally published author’s income based on royalty rates because that doesn’t factor in unearned advances. The contention here is that most advances in the current market are intended to be more than the author would earn at the standard royalty rates, meaning that the author isn’t meant to earn out. Instead, the publisher is paying a larger advance in lieu of higher royalty rates.

In theory, this sounds like a pretty good thing, doesn’t it? I mean, if the publisher offers you a $25,000 advance but doesn’t think you’d earn more than $20,000 in royalties, they’re giving you a bonus of $5,000. What’s not to like?

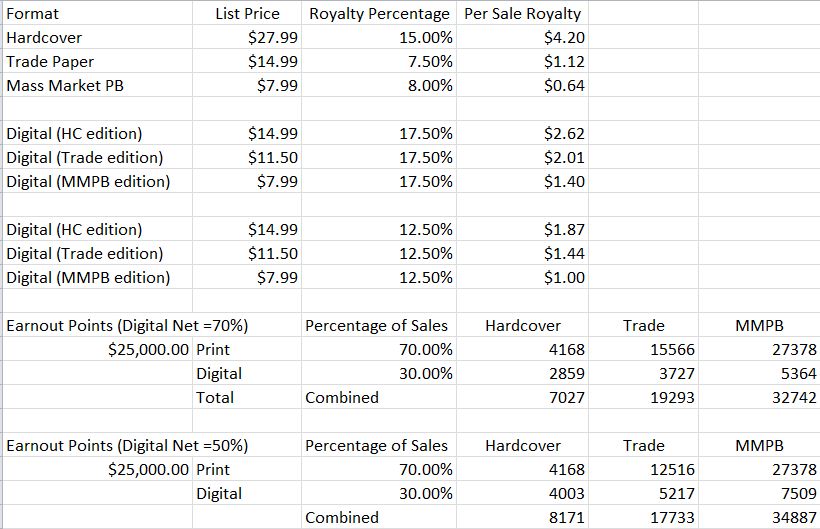

Before I answer that question, I’m going to show you a lovely little spreadsheet I developed in my spare time. (Oh, wait, I don’t have any spare time. I developed it in time I should have been using for other things. Bad Jackie, no cookie!)

The Earn-Out Worksheet

This spreadsheet is designed to help a writer figure out, based on a book’s list price, format, and royalty rate, how many copies he/she must sell to earn out a particular advance amount. It’s also designed so that you can change the breakdown of sales between print and digital based on what percentage of sales are print vs digital. A writer in genre romance might sell 40/60 print to digital while a YA or middle grade author might see a breakdown more like 75/25. I used the industry’s standard value for my “base” spreadsheet, which is 70% print, 30% digital.

I also made some basic assumptions about standard royalty rates that might not be accurate in all cases. For example, when it comes to digital books, most legacy publishers pay 25% of net. Since net depends on whether the publisher is getting 70% of the list price (most of the Big 5) from retailers or 50% of list (most of the independent publishers), 25% of net can mean either 17.5% or 12.5% of list. If you have an escalator clause (i.e., you get 25% of net up to 20,000 copies sold and then 35% of net after that), the spreadsheet formulas would have to be modified to account for that difference.

I was able to get on CPanel today, so now you can download without emailing me. Just click the link below.

Download EarnOutWorksheet.xlsx

So here’s how many copies you’d have to sell to earn out that $25,000 advance in each of the formats, assuming a 70/30 print to digital ratio. (Obviously, I can’t factor in whether or not your hardcover book goes to a trade edition and later to mass market paperback, so if you have a hardcover contract, this may not be as useful to you as to someone in trade or mmpb.)

|

Just for funsies, here’s the same calculation, but assuming a 50/50 print:digital split:

|

A few things jump out at me when I look at the results of these calculations. The first is that, if your book is going out in hardcover, you are getting a raw deal on digital royalties. I mean, like, seriously bad. The second is that, if you’re getting an advance less than $25,000, regardless of format, your publisher probably expects you to earn out. If you don’t earn out that $25,000, your book probably FAR underperformed the publisher’s expectations because, frankly, the print sale numbers you need to earn out are so low that your publisher is not going to be happy with your sell-through.

With that in mind, we’ll look at the numbers for a $100,000 advance:

|

All right! Now we’re talking about an an advance that might be pretty tough to earn out and which might have the practical effect of paying you more per sale than the royalty rates would imply. Especially if this is a mass market paperback deal, this definitely looks like a great offer.

But let’s scratch below the surface before we conclude that you’d always be wise to take this offer. Here are a few reasons that even a $100,000 advance might not be to your benefit (and I’m assuming, here, that you’re not already sitting atop the bestseller lists with a self-published novel when you get this offer.

How Long Do You Have to Earn Out?

When a publisher offers a large sum of money for your book, it’s easy to think, “Woohoo! Guaranteed money in the bank. I am absolutely certain that I am never going to make less than X dollars on this book. I should take the money and run.” You might be right, but before you assume it’s in your best interest, consider this: the initial term of a contract is seven years. This means that, although you might get $100,000 in the year you sold the book, if you don’t earn out your advance during the next seven years, you are guaranteed not to earn so much as one more penny in those seven years.

Back in the old, pre-digital days, this wasn’t that big a deal because, frankly, unless your book was selling well enough to go back for additional print runs, you only had maybe 4-6 months to sell most copies of your book. This might be less true in non-fiction, but in fiction, there’s heavy churn, especially in mass market paperback. You’ve got maybe four months on the shelves before most retailers strip your books and return them. In this world, a publisher giving you a big advance is taking a pretty significant risk. If your book doesn’t catch on in those initial four months, they are probably screwed. You, on the other hand, are sitting on $100,000 in cash. Yes, you’ll have to wait seven years to get your rights back, but in those print days, your reverted rights were practically worthless. Publishers weren’t likely to line up to buy the rights to republish your book that didn’t do well the first time, and you couldn’t publish it yourself. In this world, that big advance that might not earn out was absolutely a win for the author. If the book did well and went for additional printings, the additional royalties were just icing on the cake.

Problem is, we don’t live in that world any more. The churn in the print market is just as rapid as ever (in some cases, rapider; I know an author whose entire order was stripped by a big box retailer before it was even shelved), but the digital book is forever. In this environment, the majority of your print copies are going to sell within the first six months to a year. But your digital copies? Those can keep selling for the next six and a half years. Granted, they’re probably not going to sell at the same, healthy clip three years after release as in the first year (unless your publisher drops your sale price and does a promotion, which might move more copies, but at the expense of royalties, so there’s a trade-off there). But all in all, this means you now really have six years to earn out that $100,000 advance. Does that mean you will? No. But it does mean that you’re selling books six or seven years into your contract term and still not seeing so much as a penny in additional earnings.

If you’re still steadily selling a book or two a year to publishers at $100,000 or more a pop, the fact that you aren’t earning out your advances isn’t that big a deal. After all, you’re getting new advances to take up the slack. But that doesn’t happen to everyone. Not everyone who gets a healthy advance is going to keep getting them. When you’re looking at the possibility of not earning out an advance, you have to ask yourself what happens not in the best case scenario, but in the worst case scenario.

And the worst case is that your book sells below expectations, you don’t get more great advances, and…

You Can’t Get Your Rights Reverted

As I said above, the term of a typical contract with a NY publisher is seven years. At the end of seven years, authors can request reversion, but only if certain conditions are met. Back in the old print days, a publisher had to keep your book “in print” to retain the rights, which meant investing in another print run of your book. If your book sold poorly the first time around and you didn’t become a big name in the meantime, the likelihood that the publisher would invest in another print run was nil. You could easily get your rights reverted. Of course, you also couldn’t do anything with them, but…

Now, however, most contracts are written in such a way that no additional print copies are needed to keep your book “in print.” The fact that it’s available for sale on retail sites in digital format means it’s still in print. That doesn’t mean you can never get your rights back (at least not the way most contracts are currently written), because most contracts additionally state that a certain number of copies must sell each calendar year. If your sales drop below that threshold, you can request a reversion. The problem is that the thresholds are often pretty low. I’ve seen them as low as 250 copies. Some are more like 500. There might even be a few that generously let you request reversion at less than 1,000 copies a year.

Now, if you’ve already earned out your advance and are selling below the threshold, then there’s a pretty good chance your publisher isn’t going to try to hold onto your rights. But what if you’ve earned out only $70,000 of your $100,000? Your publisher has an incentive to squeeze as much revenue as possible out of your book, which means doing things like putting it on sale for 99 cents for a month. Quick as a flash, they’ve sold 1,000 copies, but you’re still not appreciably closer to earning another dime. And this could conceivably go on for years. (I also know of at least one author who suspects her publisher is over-reporting her digital sales because she hasn’t earned out her advance yet. She can’t afford to have an audit done, so she has to take the publishers’ word for it.)

Bottom Line

As you can see from the above analysis, I’m skeptical that an advance that can’t earn out is necessarily in an author’s best interest. It certainly can be. But you really have to ask yourself two questions:

1) If I never earn another dime from this book because the publisher retains the rights for the next 35 years, is this advance enough that I’ll be content?

2) If I do earn out the advance and continue selling copies such that I can’t get my rights back, will I be content earning only standard royalty rates on the additional copies that sell for the next 28 years?

Once you know the answer to those questions, you’ll have a better idea of how good a deal it actually is.

And if you’re Audrey Niffenegger and someone offers you $5 million? Take the money and run!

No Comments